Lessons to My Former Self (Part 1)

Not long ago, I was a pitcher in college and thought I knew everything about strength and conditioning. Oh, how wrong I was.

Since my career change, I’ve often thought back to my high school and college career and how I would have tweaked my own training to be tailored to pitching. It should go without saying that I know a lot more now than I used to, but by no means am I the “know-it-all” I was before.

Now, before I go on, I need to preface by stating that some of what I’m going to say will fly in the face of baseball traditionalists – many of whom believe that lifting weights will get a pitcher bulky, and that running in between starts is the best way to “stay in shape.” Details about hypertrophy and metabolic demands aside, I hope you can keep an open mind if you’re among this traditional baseball crew.

Also, if you haven’t noticed by now, I tend to like lists, as it makes everything *appear* more efficient. That said, here are my first two lessons to my former self:

Stop Running and Lift More – Every season tends to have its ebb and flow, but looking back, every season of mine from high school to college had the same peaks and valleys. I’d start off the season really well and throwing with good velocity for myself, but then I’d end every season with barely any strikeouts and getting bounced around in my last few starts. Now, there’s a ton of variables that could be responsible for falling apart as the season wore on. For one, I may have just been getting fatigued with each start, and there’s been studies that illustrate that the number of pitches thrown will incrementally increase their ERA throughout the season. Another reason could simply be that hitters get better as the weather warms up and they receive more and more exposure to live pitching. But, I venture to say that it was running for 25-30 minutes the day after every start for why I was becoming less and less effective.

“Wait, I thought pitchers were supposed to run? Doesn’t it flush out the lactic acid in your shoulder?”

This theory and common misperception among baseball traditionalists is flawed in every single way. First off, lactic acid is not responsible for muscle soreness. In fact, lactic acid is actually fuel for your body, and the only reason it was once thought to cause soreness has to do with some crazy scientist that experimented on frogs by shocking them and taking blood samples…and no, I’m not joking. While I won’t bore you with the details, here’s a nice little article that explains it in more detail.

Next, let’s touch on the SAID principle (specific adaptions to imposed demands). If you compare long distance running and pitching, they are completely different animals. One requires short, 2-3 second repeated bursts of high intensity with recovery of 15-20 seconds, and the other requires low, steady intensity of 20-30 minutes. When put this way, there doesn’t seem to be a whole lot of carryover, does it? Running will sap your power as your body adapts to it.

The five worst words you can say to a pitcher: "Okay guys, go run poles."

In a study that came out a few years ago, 16

Division 1 college baseball players were divided into a cardiovascular

endurance training group (ahem, running) while the other half were placed in a

speed group. During the

season, those that were in the cardiovascular endurance group saw significant decreases in power, while those that

participated in speed training saw immensely improved power production. While no study should be treated as fact, it can be theorized that speed training

and weight training would definitely improve (or maintain) levels of power...which is what you want if you’re a pitcher!

No Overhead or Barbell Lifting – While I was lucky to never really be affected by any shoulder problems, I was in the minority on my college team. Many of my teammates were often performing military presses, upright rows, barbell bench pressing, and a few others. Of course, we knew nothing about glenohumeral instability, or how our body had adapted from throwing a baseball for 18 years.

The problem with many of these exercises is that it requires a ton of shoulder mobility, and those that play overhead sports often have asymptomatic shoulder issues. This study found that 79% of asymptomatic professional pitchers had abnormal labrum features. It doesn’t take a fancy degree to tell you that if you have instability in this region, the risk/reward of overhead pressing is not in your favor.

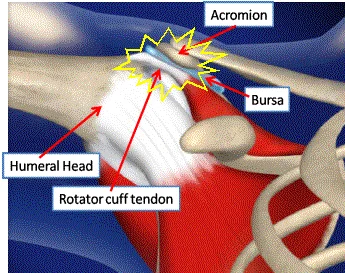

Plus, exercises such as upright rows require thoracic spine mobility, and great control of your rotator cuff to prevent shoulder impingement. While I’ll dig into this topic in a few more weeks, the picture below illustrates that if your rotator cuff isn’t preventing superior glide of your humerus, it will impinge on your supraspinatus (one of your 4 rotator cuff muscles), causing you pain.

As you can probably tell, I had a lot of fun writing this one, and I’ll be back in a few days with Part 2….which hopefully won't be as long!