Counting Facts, Instead of Calories

I was petrified when I met with my first nutrition client. Will they believe what I say? Will I meet their expectations? It's one thing to learn from a textbook and be certified, but quite another to actually coach someone.

I'm still far from a "nutrition whisperer," but I've learned a lot since I started several years ago. Instead of trying to fix whatever I *thought* was their problem, I now begin with this general algorithm:

- What's their current and previous relationship with food? (Hint: we all have one)

- Is this person getting enough sleep? (Usually not.)

- Are they adequately hydrated? (Again, usually not.)

- Are there any glaring tendencies that need to be addressed? (Like when someone puts butter in their coffee. Yup, that's a thing.)

Seems like pretty common sense, no? But if you look above, you'll see no mention of the word "calories." That's because the very last thing I'm worried about is how many calories someone needs or takes in. Instead, I'm worried about the foods they're consuming.

It adds up to....Wrong.

I've written about my general disdain for counting calories both here and here. And I'll admit that I, too, once thought of foods merely as calorie vessels. But counting calories is wildly inaccurate and fails to show the quality behind your food. After all, 100 calories from a banana is vastly different than a 100 calorie pack of Oreos.

We can now add scientific evidence that focusing on foods - and not on calories - is a healthier approach. Published about three weeks ago, here's an article featuring Dr. David Ludwig:

"Overeating does not make you fat," expert says

Attention seeking headline aside, Ludwig argues a pretty radical viewpoint: calories don't matter nearly as much as we think they do, and people gain weight from eating the wrong types of foods. Specifically, foods that are high in sugar, refined grains, and processed carbohydrates are those to blame. Consuming those foods starts a vicious cycle where insulin continually pumps any free sugar in our blood into our fat cells, instead of going where it needs to go - our brains and muscles.

Anecdotally, Ludwig's theory is the best explanation to describe what I've seen when people count calories. If people do lose weight, they tend to gain it back when they fall out of the counting habit. But more often than not, people fail to lose weight (or even gain) while complaining about how hungry they are. Plus, if the obesity problem were really a "calories in/calories out" science equation wouldn't it be a lot easier to solve?

Food quality clearly matters, but I'd like to take Dr. Ludwig's message one step further - it's not only what we're eating, but the context that we're eating our food.

Are we eating with friends or alone? When we're eating with friends, are we socializing or looking at our phones the entire time? When we eat indulgent foods are they low quality (Snickers bars) or high quality (chocolate with 70% cacao)? How's our stress levels and could those trigger our eating patterns? The answers aren't easy, but I ask because of the French.

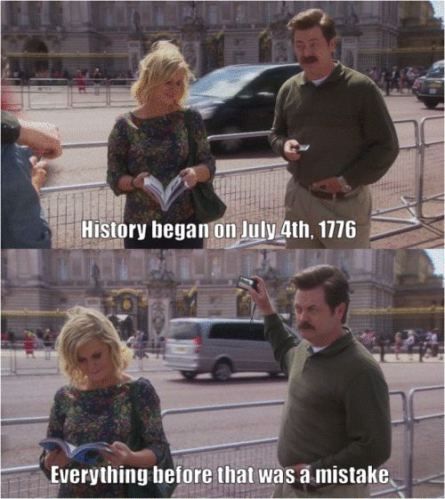

Even though I have a Ron Swanson-esque distrust of the country at hand, the French Paradox is quite fascinating. In short, French diets are high in saturated fat, alcohol and anything indulgent. But they have one of the lowest rates of Coronary Heart Disease in the world. What gives?

While the French may have a very indulgent diet, they actually follow a lot of the principles that can make any diet successful. Instead of looking at food as a problem, the French look at food as a source of pleasure (and no, not the type you'll feel bad about 5 minutes later). They also abide by strict rules: they don't go back for seconds, they don't snack, and they often eat communally. It makes them enjoy their food, taste it, and forces them to eat high quality ingredients to maximize their experience. Even though parts of this approach are at odds with Dr. Ludwig's article above (breads, pastries, and treats are no strangers in the French diet), other elements (plenty of unsaturated fat and a focus on high quality foods) are very similar.

By choosing foods based on calories - which, in essence, is exactly what calorie counting is - it's proof that when all you have is a hammer, everything is a nail. But by choosing what foods we're eating, realizing it's more than the sum of its parts, and the context surrounding our consumption, it gives us more tools to use.

It's time to expand our toolbox.